Did the Mongols really hate Islam, or just the Muslims’ arrogance?

Written by Hassam Munir

Many Muslims today believe that the 13th-century Mongols reserved a special hatred for Islam and its adherents. This attitude is now almost 800 years old – “Islam and the Muslims have been afflicted during this period with calamities wherewith no people hath been visited,” penned Ibn Athīr in 1220 CE[1] – it has lingered on as the consequences of the Mongol conquests have continued to unfold in the Muslim world, right up to the present day.

But is it really true?

The Mongols were exposed to Islam long before they even thought of conquering the Muslim world. By the time Temujin – the boy who would one day become Genghis Khan – was born in the 1160s, the Mongols and their relatives from other tribes had already for centuries been serving as guards for the trade caravans of Muslim merchants travelling along the Silk Road. Even among the people of the steppe (including the Mongols and other tribes) who lived a more traditional life, many had embraced Islam. Many of them become some of Genghis Khan’s strongest supporters, and three of them even took part in the famous Baljuna Covenant, a solemn oath of allegiance sworn by the shore of Lake Baljuna in 1203 during the most difficult test of Genghis Khan’s life.[2]

Genghis Khan could look for even stronger Muslim support among the Uyghur people, who lived in modern-day Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and northwestern China. In the early 13th century they were ruled over by a Buddhist sub-group of the Khitan tribe known to the Mongols as the Kara Khitan (“Black Khitan”). The Khitan were distant cousins of the Mongols. They were originally from Manchuria (northern China) but had been driven out by the Jurched tribe. Guchlug, a notable of the Naiman tribe and a Christian, had recently fled his homeland after his tribe was defeated by the Mongols. He headed to Uyghur territory, where he soon married the daughter of the chief of the Black Khitan and then overthrew his father-in-law, taking control himself. To keep attention away from his own indecent rise to power, Guchlug turned the public attention to a common enemy of Christians and Buddhists – the Uyghur Muslims.

Guchlug immediately began to persecute his Muslim subjects, outlawing the adhan (call to prayer), salah (the prayer itself), and religious education. When he left the capital city of his empire, Balasagun, on a military campaign, the Muslims closed the city gates behind him and barred him from re-entering. Furious, Guchlug returned and laid siege to his own capital, conquered it, and then destroyed much of it. Desperately, the Uyghurs now reached out to the only local ruler powerful enough to help them: Genghis Khan. Genghis Khan immediately sent an army of 20,000 Mongol soldiers under one of his most competent generals, Jebe, marching 2,500 miles across Asia to support the persecuted Muslims. The Mongols quickly crushed Guchlug’s forces and Guchlug himself was executed somewhere in the Himalayas in Kashmir.

Because the Mongols had come in support of a persecuted religious group, they did not plunder, destroy property or assault civilians as they usually would. After the victory, the Mongols sent a messenger to Kashgar, the cultural capital city of the Uyghurs, to declare complete religious freedom. The Muslim population of Kashgar celebrated and declared that the Mongols were “one of the mercies of the Lord.”[3]

Clearly, then, the Mongols weren’t vehemently anti-Islam, as many in the Muslim community continue to believe. But this does leave a very important question unanswered: why did the Mongols destroy so much of classical Muslim civilization?

Genghis Khan offered his own explanation one day in March 1220. He had just conquered Bukhara, a city that was important symbolically as a famous centre of Islamic learning and culture and strategically as a major centre of trade located on the Silk Road. It was the first Muslim city that he had conquered, and he sought to take the opportunity to make an impression on Muslims everywhere. Generally, it was his practice to never personally enter a city he had conquered. However, in Bukhara he rode into the city himself, leading his cavalry right up to its centre.

The Mongols were in Bukhara for a reason: revenge. Bukhara was one of the primary cities of the Khawarezmid Empire, one of the many come-and-go Muslim empires of that era. Because the Khawarezmids controlled much of the Silk Road between China and the Middle East, they were exceptionally powerful – and exceptionally arrogant. The Khawarezmid sultan ‘Alā ad-Dīn Muhammad II (r. 1200-1220), after expanding the power of his empire so much during his reign, in the end sealed its fate by looting a Mongol trade caravan and disfiguring the faces of the ambassadors sent by Genghis Khan to negotiate peaceful trade relations. It was the sultan’s arrogance – not his religion – that the Mongols would soon come to destroy.[4]

Only months later, Genghis Khan was sitting triumphantly on top of his horse in the middle of Bukhara. Gathered around him were the civilians of Bukhara, who had surrendered their city to him after the 20,000-man Turkic army of their sultan had fled the city, too terrified to defend it from the approaching Mongol army. Genghis Khan asked whether the large, beautiful building he saw in front of him was the home of the sultan. He was told that it was a mosque – the Grand Mosque of Bukhara. He dismounted from his horse and walked into the mosque, the first and only time he entered a religious building in his life (as far as we know). Genghis Khan ordered the Islamic scholars and students of ‘ulūm ad-dīn (religious sciences) who were gathered in the mosque to feed his horses, and in exchange he personally guaranteed that they would be safe from persecution.

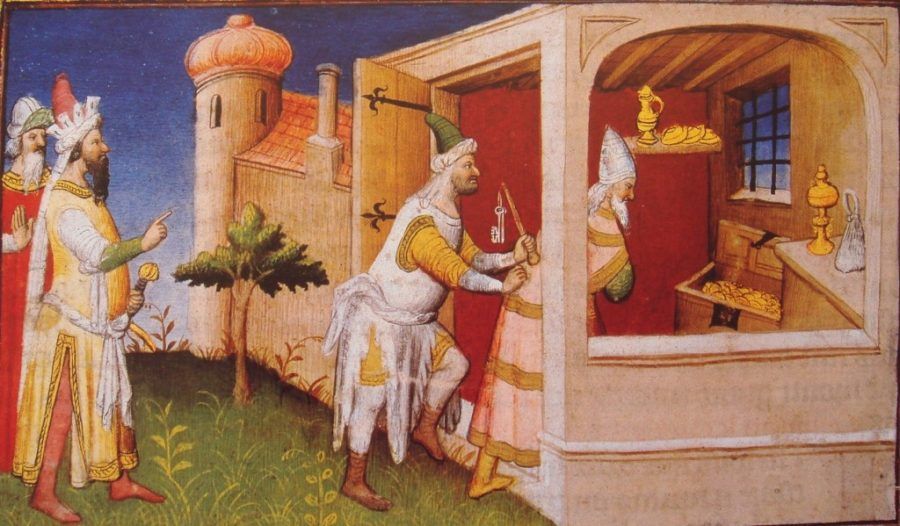

The awe-inspiring Mongol leader then asked for the 280 richest people in the city to be brought to him. Once they and others had gathered in the mosque, Genghis Khan climbed the mimbar (pulpit) and addressed them through his interpreters. He talked about the sins of Sultan ‘Alā ad-Dīn Muhammad II and the sins of his new subjects in Bukhara. “It is the great ones among you who have committed these sins,” he said, and the common people weren’t to blame for the city’s fate. “If you had not committed great sins, God would not have sent a punishment like me upon you.” He then assigned one of his warriors to each of the 280 wealthy men to accompany them to wherever they were hiding their hoarded wealth and to bring it to him.[5]

Genghis Khan then took his soldiers and proceeded to the citadel of the city, where about 500 soldiers still loyal to the Khawarezmids had locked themselves up. This is where the Mongols would really put on a display of their anger at the sultan’s arrogance. They rolled in the siege equipment that they had mastered during their earlier campaigns in China, weapons that these Muslim soldiers had never seen and that were designed to not only destroy but to terrorize. Ata-Malik Juvaini, a Persian eyewitness who recorded these events, summed up the fate of the soldiers in the citadel: they “drowned in the sea of annihilation.”[6]

Genghis Khan’s army moved fast, but his reputation moved faster. Samarqand, the nearby capital of the Khawarezmid Empire, surrendered on peaceful terms before the Mongols arrived. Sultan ‘Alā ad-Dīn Muhammad II abandoned his throne and fled for his life to a small island in the Caspian Sea, where he died. In just one year, the Mongols completely wiped the powerful Khawarezmid Empire off the map. Over the next four years, they continued their conquest of Muslim civilization in the east, taking one Muslim city after another. Urgench, Balkh, Merv, Nishapur, Herat, Bamiyan, Ghazni, Peshawar, Tabriz, Derbent, and many others either surrendered or were taken by force. Genghis Khan stopped only in Multan (in modern-day Pakistan), from where he had planned to invade the territory of the Delhi Sultanate, first Muslim dynasty to rule northern India. However, the Mongols found the heat of the Punjab unbearable, so they abandoned the campaign and headed north.[7]

Genghis Khan never returned to Central Asia or the Middle East, but his grandsons picked up where he had left off. In 1253, exactly thirty years after Genghis Khan’s return from Multan, his grandson Mongke Khan called a khuriltai, a traditional council of Mongol leaders, at Karakorum, the capital of their massive empire. After Genghis Khan’s death, his sons had become engaged in a power struggle that had brought the Mongol conquests grinding to a halt. Mongke Khan was the first leader in many years to be recognized by virtually all of the Mongols, and he was now ready to continue the Mongol conquests. At the khuriltai, he ordered his brother Kublai to start the invasion of the Sung dynasty’s territory in China. He ordered Hulagu, a younger brother, to resume the campaign against Muslim civilization. However, this time Mongke didn’t just need the Muslim fringe territory in Central Asia. This time he wanted the jewels of classical Muslim civilization: Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo.[8]

Hulagu may in fact have had some anti-Islamic prejudices, considering the influence of his Christian mother and wife and, more importantly, considering the devastation he caused as he conquered the Middle East. After laying waste to much of Iran – including completely eliminating the legendary network of the Nizari Ismaili terrorists known as the Hashīshiyūn (Assassins) – he arrived outside Baghdad in January 1258. He had already sent messengers to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, al-Musta’sim (r. 1242-1258), demanding his surrender. But al-Musta’sim refused to surrender, laughing away Hulagu’s threats and replying to him that Muslims from across the world would come to the defense of Baghdad if need be. Hulagu made use of Christians – soldiers from Armenia and Georgia as well as informants from within Baghdad – in his conquest of Baghdad. The city was taken on February 10, 1258 and looted for 17 days before being burnt down. Al-Musta’sim was trampled to death by Mongol horses on February 20th.

But before he had him killed, Hulagu did explain to Musta’sim – in his own way – why he believed the Muslims had lost Baghdad. Hulagu had Musta’sim imprisoned and starved until he eventually started to beg for food. Then Hulagu had some of Musta’sim’s treasure brought to him and offered him a gold nugget to eat. When Musta’sim was unable to eat it (for obvious reasons), Hulagu berated the former caliph for hoarding his wealth instead of using it to defend himself and his people against the Mongols. Then Musta’sim met his fate.[9] Hulagu’s army then took Damascus (through a peaceful surrender) and much of Syria, before they were finally defeated by a Mamluk army from Egypt at the Battle of Ayn Jalut on September 3, 1260. Mongke Khan had passed away exactly a year earlier, and Hulagu still hadn’t returned from the khuriltai held in Mongolia to select a new Mongol leader.[10]

It had been four decades since Genghis Khan’s conquest of Bukhara, and in that time the Mongols had brought Muslim civilization to the lowest point in its history. Neither in Europe nor in the Far East – the two other important regions that the Mongols had penetrated – was the conquest as destructive. This can (and probably did) lead many Muslims to believe that the Mongols must have exclusively hated Islam and reserved their rage for its adherents. But this doesn’t stand up against the historical evidence presented here: it’s not Islam that the Mongols couldn’t stand, but the arrogance of the Muslim elite.

One final piece of evidence that supports this is the fact that some of the strongest opposition to Hulagu’s ravaging of Iraq and Syria came from his own cousin, Berke Khan, the ruler of the Golden Horde (the northwestern part of the Mongol Empire). A few years earlier, Berke, on a return journey from Europe to Mongolia to attend a khuriltai, had stopped in Bukhara and met some Islamic scholars. He then embraced Islam and, upon hearing of his cousin’s destruction of Baghdad a few years later, vowed to get revenge on behalf of the Muslims. But even Hulagu’s own descendants, in just a few generations, had embraced Islam, and so had many Mongol commoners.

The lesson in this for the Muslim community today is to remain conscious of its own flaws, flaws that are often discussed in the Qur’ān and in the sunnah of Prophet Muhammad (salAllahu alayhi wa sallam), flaws that can be exploited by hostile forces. And the first thing that needs to be addressed when the flaws are exploited is not the “evil” or “Islamophobic” nature of the people exploiting them but the reason these flaws exist in the first place. Many Muslims thought the coming of the Mongols was a punishment from God for their sins, and yet it seems that very few thought of the sins they were being punished for. The Muslims’ flaw (or sin, if you will) in this case was clearly their arrogance – and Genghis Khan literally delivered that message to them in Bukhara. But it was an inconvenient truth, and it was buried away in one Muslim city after another until it was too late for all of them.

That attitude is what the Mongols came to destroy, not Islam.

IMAGE CREDITS

Featured: “Hulagu In Bagdad” by Maître de la Mazarine – “Le Livre des Merveilles”, 15th century, reproduction in “Le Livre des Merveilles”, Marie-Therese Gousset.. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HulaguInBagdad.JPG#/media/File:HulaguInBagdad.JPG

Second: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-M47QY1lwlmE/UgOU8xeDxiI/AAAAAAAAA-g/cXy9BcXpw6g/s1600/Khan+at+Bukhara.jpg

Third: “Persian painting of Hülegü’s army attacking city with siege engine” by Unknown – https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4d/Persian_painting_of_H%C3%BCleg%C3%BC%E2%80%99s_army_attacking_city_with_siege_engine.jpg/419px-Persian_painting_of_H%C3%BCleg%C3%BC%E2%80%99s_army_attacking_city_with_siege_engine.jpg

Source http://www.ihistory.co/did-the-mongols-really-hate-islam-or-just-the-muslims-arrogance/

REFERENCES

[1] Edward G. Browne, A Literary History of Persia, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1902), Vol. II, pp. 427-431.

[2] Jack Weatherford, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, (New York: Crown Publishers, 2004), p. 105.

[3] Ibid, pp. 159-161.

[4] Ibid, p. 37.

[5] Ibid, pp. 39-40.

[6] Ibid, p. 42.

[7] Ibid, p. 186.

[8] Ibid, p. 249.

[9] Ibid, pp. 254-58.

[10] Ibid, p. 260.