EDUCATION IN THE OLD MUSLIM WORLD

By Faisal Malik

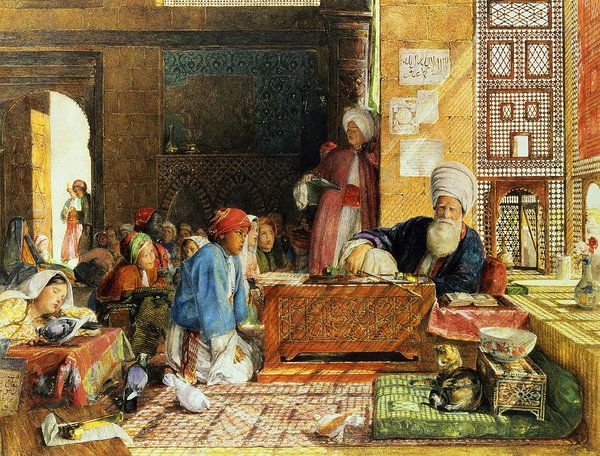

Schools became prevalent in many parts of the Muslim world and were generally accessible to various levels of society. Records show that during the period of Mamluk rule, there were schools in Cairo and Damascus for educating women and in the 13th century, education was provided for elderly, divorced, and widowed women. [1]At the time of Muslim rule in Spain, in Cordoba alone there are reported to have been 17 universities and 70 public libraries with hundreds of thousands of books.[2] During the 14th and 15th centuries CE, there are reports that in Delhi alone there were close to a thousand madaaris and education was accessible to all classes of society, including slaves.[3] Many non-Muslims in India during the Mughal period would enroll in madaaris and makaatib (plural of maktab, a type of primary school for children).[4] One colonial official reported in 1857 his amazement at the number of Hindus who were attending Muslim-run schools in the Punjab region.[5] During the 18th century, European tourists visiting places such as Cairo recorded their surprise at the huge percentage of the population that was literate.[6] Reports from French researchers in Algeria during the beginning of the French occupation of Algeria in the 19th century noted that the proportion of literate people in Algeria was higher than that in France.[7] These are just some examples of the vast networks of schools that were prevalent in many parts of the Muslim world. However, the question arises: what exactly was being taught in these schools?

Al-Ma’qul and Al-Manqul: The rational and the transmitted

When discussing the curriculum of what was being taught and studied in the madaaris and other schools in the Muslim world, it is important to note that, unlike the division between religion and the secular that would eventually mark the Western world, traditional Muslim societies did not divide knowledge in this way. In Muslim civilization, religion was viewed as encompassing a holistic view of reality in which reason and rational thought were integrated with sacred knowledge. The curricula of madaaris and other schools in the Muslim world were generally divided between the ulum al-ma’qul (the rational sciences) and ulum al-manqul (the transmitted sciences).[8] Many subjects that would in modern times be classified as secular—such as math, medicine, and others—in traditional Muslim societies would generally fall under the ulum al-ma’qul.[9] It is important to note that, although many of the ulum al-ma’qul (e.g., math, medicine, etc.) would in contemporary times be classified as secular sciences, these subjects were taught in the Muslim world within an Islamic paradigm. Muslim society never saw a need to divorce subjects from religion; therefore, the ulum al-ma’qul were considered a sub-branch of religious learning and Muslim thinkers regarded scientific research as a means of exploring religious truths[10] and contemplating God’s creation.

While speaking of the study of medicine, astronomy, or other sciences as grounded in an Islamic paradigm might seem strange to some, it is important to note that no subject can be taught outside of a paradigm and a worldview. While many disciplines studied and taught in the West and secular universities often claim universality, deep analysis would find them grounded in a various array of paradigms and worldviews, whether positivism, reductionism, relativism, historicism, etc.

Just glimpsing the lives and works of prominent thinkers who lived during the period when Muslim civilization flourished, one can find many instances that demonstrate how Muslim societies were established on an integrative approach to knowledge that combined religion, reason, science, ethics, and metaphysics.

Ibn Sina, the famous Muslim polymath who lived in the 10th and 11th centuries, divided theoretical philosophy in relation to matter and motion into three types of science: natural, mathematical, and theological/metaphysical.[11] He did not see these sciences as secular and religious; rather, he saw them as divisions within a larger framework of knowledge. It is noteworthy that while Ibn Sina believed that theology/metaphysics was the highest of sciences and natural sciences was the lowest,[12] this did not hinder his approach to the natural sciences, with his work on medicine (Qanun fi al-Tibb) becoming the standard textbook on medicine in Europe for several centuries.[13]

The famous theologian Al-Ghazali, who lived just a generation after Ibn Sina, praised the study of medicine and math and claimed that it was a communal obligation for some people within a community to study these sciences. For Al-Ghazali, any field of study that was necessary for developing communities—such as medicine, math, agricultural, and others—was considered theologically a communal religious obligation and at least some members of every community needed to be skilled in such sciences.[14]

The 14th-century historian and sociologist Ibn Khaldun wrote in his Al Muqaddimah about the various sciences that were being studied in the Muslim world at his time and noted that the sciences that were included amongst the ulum al-ma’qul were logic, physics, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, medicine, algebra, optics, and others.[15] He noted that there existed a high regard for math in some Muslim communities and children were taught the subject at an early age.[16] It is also noteworthy that, in outlining the various sciences that were being studied in the Muslim world, Ibn Khaldun also observed that, throughout Muslim civilization, the Qur’an played a central role in the education of children.[17] One example of the centrality and impact of Qur’anic education in the Muslim world can be seen in an account of Francis Moore, an employee of the Royal African Company of England, who noted in the 1730s that, in the region of Senegambia, the local population was more learned in Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, than Europeans were in Latin.[18] Ibn Khaldun’s outline of the various subjects being taught in the Muslim world, along with recording the centrality of the Qu’ran in the education system, shows that Muslim civilization saw no contradiction between religious faith and science, reason and revelation, and had developed a civilization that integrated knowledge into a unified system that was not bifurcated into a secular and religious divide.

The integrative approach to reason, science, and revelation that existed in Muslim societies facilitated the creation of educational institutes that advanced knowledge and scientific inquiry. Between the 9th and 12th centuries, there were more philosophical, medical, historical, astronomical, and geographic works written in Arabic than in any other language.[19] Under Abbasid rule, scientific research was often supported by the government[20] and the Baytul Hikma (House of Wisdom) was a famous observatory, research, and learning center.[21] During the Seljuk period, one could find hospitals and astronomical observatories adjacent to madaaris.[22] Under the Ottomans, madaaris dedicated to the study of medicine were established, such as the Suleymaniye Medical Madrasa set up by Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566).[23] Under the Mughal ruler Akbar, it was decreed that every boy should learn arithmetic, agriculture, geometry, astronomy, medicine, and logic along with other subjects.[24] The Dars-e-Nizami, a curriculum devised by the 18th-century scholar Mullah Nizamuddin Sahlavi, which hundreds of madaaris associate with in contemporary times, originally had engineering, astronomy, and medicine in its curriculum.[25]

CONTINUE READING

REFERENCES

[1] Cook, Classical Foundations of Islamic Educational Thought, 244.

[2] Ahmed Basheer “Contributions of Muslim Physicians and Other Scholars: 700-1600AC” in Muslim Contributions to World Civilization, ed. Syed A.Ahsani, Ahmed Basheer, and Dilnawaz A. Siddiqui (United Kingdom: International Institute of Islamic Thought, Association of Muslim Social Scientists, 2005), 73.

[3] Kaur, Madrasa Education In India, 21.

[4] Kaur, Madrasa Education In India, 92 & Langohr, Vickie (2005) “Colonial Education Systems and the Spread of Local Religious Movements: The Cases of British Egypt and Punjab.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 47, no. 1, p. 169.

[5] Vickie Langohr, “Colonial Education Systems and the Spread of Local Religious Movements,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 47, no. 1 (2005), 168, 169.

[6] Ihsanoglu, History of the Ottoman State, Society & Civilization Vol. 2, p. 247.

[7] Ibid., 247-248.

[8] Cook, Classical Foundations of Islamic Educational Thought, XX & Francis Robinson, “Ottomans-Safavids-Mughals: Shared Knowledge and Connective Systems,” Journal of Islamic Studies 8, no. 2 (1997), 152.

[9] Cook, Classical Foundations of Islamic Educational Thought, XX & Kaur, Madrasa Education In India: A Study of Its Past and Present, 170.

[10] Cook, Classical Foundations of Islamic Educational Thought, XX.

[11] Al Zeera, Wholeness and Holiness in Education, 69.

[12] Ibid., 69.

[13] Ahmed “Contributions of Muslim Physicians and Other Scholars,” 80.

[14] Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali, Kitab Al-‘Ilm, 38.

[15] Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 370-390.

[16] Ibid., 376.

[17] Ibid., 422-424.

[18] Ware III, Rudolph T., The Walking Qur’an: Islamic Education, Embodied Knowledge, and History in West Africa (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), p. 106.

[19] Ahmed, “Contributions of Muslim Physicians and Other Scholars,” 87.

[20] Ibid., 76.

[21] Kaur, Madrasa Education In India, 7.

[22] Ihsanoglu, History of the Ottoman State, Society & Civilization Vol. 2, 373.

[23] Ibid., 391, 405.

[24] Kaur, Madrasa Education In India, 34.

[25] Ibid., p. 52 & Hamid Mahmood, The Dars-E-Nizami and the Transnational Madaris in Britain (Queen Mary: University of London, 2012), 9, 10, 78 & Qasmi, Madrasa Education Framework, 49, 55-57.