Facts On How Muslim Societies In Medieval Times Kept It Clean

Compiled by Cinthia Mascarell

Medieval Times Are Often Imagined As Smelly, Dark And Impure, But In The Muslim Civilization Of The 10th Century People Were Very Concerned About Hygiene

When the Crusaders of Western Europe arrived in the Holy Land in 1096, in what is called the First Crusade, the Arabs of the Middle East were more impressed by their stench than by their religious zeal. The armies of the Crusaders, plagued by diseases, included not only true believers and just people, but also, according to the report of the medieval chronicler Albert de Aix in his Hierosolymita History, “adulterers, murderers, perjuries and thieves.” Few had received any education at all. Ignoring even the rudiments of science, mathematics, medicine, philosophy and hygiene, they knew nothing about the operation of that prince of medieval scientific devices, the astrolabe, which captured the movements of the three-dimensional universe on his bronze faceplate ; As a result, they could not even date their most important religious holiday, Passover, nor accurately tell the time of day.

Celestial phenomena (shooting stars, ball lightning, an eclipse of the sun) terrified them. Their forebears had long since lost the ability to read Greek, thus breaking off intellectual relations with the learning of antiquity. Education had all but collapsed, save for a handful of cathedral schools clinging to innovations introduced three hundred years earlier under Charlemagne. The scholar-monks at the West’s leading center of mathematical studies, the cathedral school of Laon, had no grasp of the meaning or use of zero.

One of the crusaders’ greatest offenses to Arabs’ sensibilities was their total disregard for personal hygiene. Their noblest knights boasted of bathing no more than four times a year; their diet consisted mainly of monotonous rations of gruel and whatever else they could forage en route; Medical care often involved exorcism or amputation of affected limbs. When the Black Death struck Europe in the mid-fourteenth century, it unleashed social chaos. Without a real notion of contagion or hygiene, one-third of the population died without knowing why. The mass casualties induced a frenzy of violence, typified by the burning of Jews suspected of having induced the disease through witchcraft.

The Book of Instruction, an informative memoir by the Syrian princeling Usama ibn Munqidh, who came to know the Crusaders in battle and in repose, records two instances in which a local physician’s sound advice was ignored in favor of Christian methodologies. In the first, the Franks simply lopped off a knight’s mildly infected leg with an axe; in the second, they carved a cross into an ill woman’s skull before rubbing it with salt. Both patients died on the spot, at which point the Arab doctor asked, “‘Do you need anything else from me?’ ‘No,’ they said. And so I left, having learned about their medicine things I had never known before.”

Disease was viewed as divine punishment for the sins of man, rather than as a condition to be addressed or ameliorated through human intervention. The few tentative efforts to adopt the technological novelties starting to trickle in slowly from the Arab world, among them the water clock that Caliph Harun al-Rashid sent as a gift to Charlemagne in 801, were either dismissed as curiosities or condemned as Black Magic. As far as medieval Christians were concerned, God was the sole determinant force in their daily lives; there was no reason, then, to explore the nature of things—and thus, no science.

In marked contrast, the Muslims put a premium on cleanliness and dietary regime. The ritual cleansing of the body precedes each of the five daily prayers, a requirement that sparked the development of sophisticated public-water projects and ingenious engineering techniques. Religious law proscribed a number of unhealthy practices, including the consumption of alcohol, while a large collection of sayings and practices ascribed to the Prophet Muhammad, later collated as the tibb al-Nabi, or The Medicine of the Prophet, provided a general blueprint for healthy living and abstemious behavior.

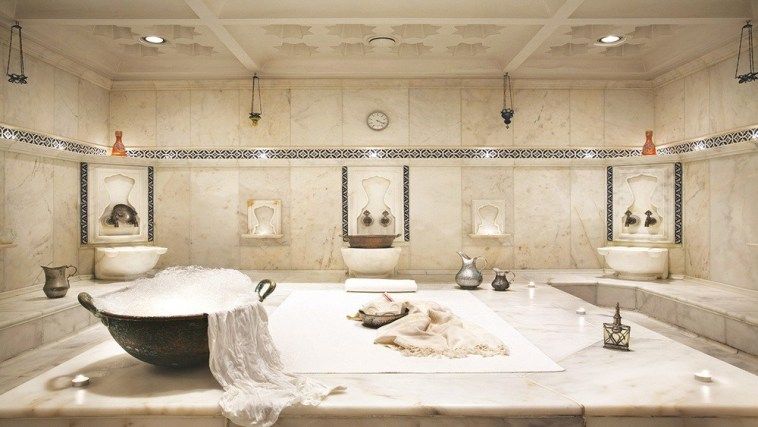

Hygiene and cleanliness was very important in the Muslim world, partly because Muslims have to perform ritual washing (wudhu) before their five daily prayers. The Hadith (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad) states that cleanliness is half of faith. The Muslims followed the Roman tradition of public baths at a time when the advances of the Romans were often neglected in Western Europe. For example, as well as supplying its half a million inhabitants with running water, Cordoba in Spain had 300 public baths known as hammams. Turkish baths, which are now popular across Europe, followed this tradition.

Cordoba in Muslim Spain was a city of over half a million inhabitants with street lighting and running water. At the same time 10,000 Londoners lived in timber-framed houses and used the river as their sewer.

Muslims were going to beauty parlours, using deodorants and drinking from glasses, at a time when English books of behaviour were still telling page-boys not to pick their nose over their food, spit on the table, or throw uneaten food onto the floor.

Cosmetic Products Used In Muslim Civilization A Thousand Years Ago Could Compete With What We Have Today

In Muslim Spain, Andalusia, in the city of Cordoba lived the famous physician and surgeon, Al-Zahrawi (936-1013 CE), Latinized as Albucassis.

He wrote a monumental work, a medical encyclopaedia entitled Al-Tasreef, in 30 volumes, which was translated into Latin and used as the main medical textbook in most Universities of Europe from the 12th-17th century. This book influenced many authors in both the East and in Europe.

In the 19th volume of Al-Tasreef a chapter was devoted completely to cosmetics and is the first original Muslim work in cosmetology.

Zahrawi’s contribution to medicated cosmetics include under-arm deodorants, hair removing sticks and hand lotions. Hair dyes are mentioned turning blond hair to black and hair care is included, even for correcting kinky or curly hair. He even mentioned the benefits of suntan lotions, describing their ingredients in detail.

For bad breath resulting from eating onions and garlic he suggested cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom and chewing on coriander leaves. Another remedy for bad breath was fried cheese in olive oil seasoned with powdered cloves.

In the book he also included methods for strengthening the gums and bleaching the teeth.

Zahrawi considered cosmetics a definite branch of medication (Adwiyat Al-Zinah). He deals with perfumes, scented aromatics and incense. There were perfumed stocks rolled and pressed into special moulds, perhaps the earliest antecedents of present day lipsticks and solid deodorants. He used oily substances called Adhan for medication and beautification. There are many Hadiths of the Prophet (pbuh) which refer to cleanliness, management of dress, and care of hair and body. On this basis Zahrawi described the care and beautification of hair, skin, teeth and other parts of the body, all within the boundaries of Islam.

Other utilities which we tend to consider as part of the twentieth century but which were present in Muslim Spain and which are described by Zahrawi include nasal sprays, mouth washes and hand creams.

A 13th-Century Robotic Wudhu’ Machine That Looked Like A Peacock Shot Eight Spurts Of Water From Its Head – Just Enough To Wash With

The ritual cleansing of the body precedes each of the five daily prayers, a requirement that led to the development of sophisticated public water projects and clever engineering techniques.

Al-Jazari was the most outstanding mechanical engineer of his time. His full name was Badi’ al-Zaman Abu-‘l-‘Izz Ibn Isma’il Ibn al-Razzaz al-Jazari. He lived in Diyar-Bakir (in Turkey) during late 12th century-early 13th century CE.

He was called Al-Jazari after the place of his birth, Al-Jazira, the area lying between the Tigris and the Euphrates in Mesopotamia. Like his father before him, he served the Artuqid kings of Diyar-Bakir for several decades (at least between 570 and 597 H/1174-1200 CE) as a mechanical engineer. In 1206, he completed an outstanding book on engineering entitled Al-Jami’ bayn al-‘ilm wa-‘l-‘amal al-nafi’ fi sinat’at al-hiyal in Arabic. It was a compendium of theoretical and practical mechanics. George Sarton writes: “This treatise is the most elaborate of its kind and may be considered the climax of this line of Muslim achievement” (Introduction to the History of Science, 1927, vol. 2, p. 510).

Al-Jazari’s book is distinctive in its practical aspect because the author was a competent engineer and skilled craftsman. The book describes various devices in minute detail, providing hence an invaluable contribution in the history of engineering.

Al-Jazari described fifty mechanical devices in six different categories, including water clocks, hand washing device (wudhu’ machine) and machines for raising water, etc. Following the “World of Islam Festival” held in the United Kingdom in 1976, a tribute was paid to Al-Jazari when the London Science Museum showed a successfully reconstructed working model of his famous “Water Clock.”

Al-Kindi, An Iraqi Scholar, Wrote A Book On Perfumes, Recipes For Fragrant Oils, Creams And Scented Waters

Al-Kindi; the Arabic scientist with immense contribution and influence in the world of perfumery.

Al-Kindi lived between 801 and 873 AD, born in Kufa, Abbasid Caliphate which is now known as Iraq. He was educated in Baghdad and grew to become a very prominent figure and a number of Abbasid Caliphs appointed him to carry out and also oversee the translation of scientific and philosophical texts which were then in Greek into Arabic language. It is widely believed that his role in the translation work and deep contact with the Greek Philosophy had a great influence in him in terms of intellectual development. This interaction enabled him to write hundreds of original papers on a wide range of subjects and topics. Al- Kindi has written on subjects such as Metaphysics, logic, psychology, ethics, Pharmacology, mathematics, optics, medicine, astronomy and astrology. He also wrote on practical topics such as perfumes, jewels, glass, tides, and earthquakes among many others. Al-Kindi worn several hats; he was a mathematician, musician, astronomer, physicist, pioneer cryptography. In his lifetime, he is believed to have written more than two hundred and sixty books with his influence in fields of philosophy, medicine, physics, music and mathematics having a far reaching effect for a number of centuries.

Al-Kindi is described as a person who had great interest in perfumes and scented products. He carried out extensive research in this area and through experiments managed to extract a number of perfumes. Through his study of several plants and flowers, he learnt that a variety of scent products can be produced. Many of the plant products that he experimented on ended up producing very useful cosmetics as well as pharmaceutical products. Many consider him as the pioneers of the science of perfumery.

He is credited with coming up with several techniques which made the production of perfumes. Through combination of raw materials from different plants several new scents were created. His work was advanced by several scientists and through that they have formed the basis of most of the perfumes and scents that used today in different parts of the world. The number of records that he produced over the period of time in the science of perfumery were great influence in the field and continued to be referred in the academic field and also in the production of perfumes and scents in different parts of the world. One of the widely used materials is the book called “The Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations.” In this book there are hundreds of recipes that can be used in preparations of perfumes and scented products. Some of the recipes include fragrant oils, aromatic water, camphor, salves and also some relatively cheaper alternatives to expensive drugs. These recipes have been widely used in preparation of perfumes, with some of the products in the market today being made using Al-Kindi methods with slight adjustments to meet the needs and preferences of the cosmetic users today.

His great work in natural perfumery makes him one of the greatest perfumist in the history of cosmetics. Also, the father of natural perfumery, the world of cosmetics has been greatly influenced by his experiments and productions. It is highly likely that some of the products you are using today can in one way or another be traced to his methodologies and recipes. His name will live forever, more so because he is associated with a product that makes people feel good about themselves and also boosts their confidence.

The knowledge about perfumes made its way from the Muslim world to southern France, which had the perfect climate and soil for perfume making.

More Than 1,000 Years Ago, The Muslim Musician And Fashion Icon, Ziryab, Introduced Toothpaste To Al-Andalus

Ziryab’s birth name was Abu al-Hassan. He was born in 789, but his place of birth is debated. Historians throughout the ages have claimed him to be Arab, Persian, Kurdish, and Black African. No doubt this confusion exists as each group wants to claim him as their own. His nickname of Ziryab means “Blackbird” in Arabic. He got this nickname because of his dark skin and beautiful singing voice.

He was originally a court entertainer during the reign of Harun al-Rashid, the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. The story has it that he was such a good musician that others in the royal court were jealous of him enough to exile him, lest they lose their jobs to his immense talent. Once exiled, he sought refuge in Africa, offering his skills to whatever local ruler was willing to patronize him. He got his big break, however, when he was invited to the Umayyad emirate of Spain, by the Umayyad emir al-Hakam.

When Ziryab finally made it to al-Andalus, he was welcomed by al-Hakam’s successor, Abd al-Rahman II. Abd al-Rahman was fascinated by Ziryab’s talents and immediately made him a major part of the royal court in Cordoba. Ziryab was given a hefty salary, a palace to live in, and major control over the cultural development of al-Andalus.

He established an institute to educate people in musical arts and entertainment. At the institute, he took wealthy and poor students alike. He taught the traditional musical styles and songs of his old home, Baghdad, but also added his own twist to many songs, innovating as he went along. He even added a fifth string to the traditional instrument, the lute. This later paved the way for the development of the guitar. He was respected by all in al-Andalus at the time as the foremost musician of the day.

He revolutionized in fashion and food: Like today’s superstar musicians, Ziryab was also a fashion and cultural icon. People looked to him for the latest and greatest forms of dress, hairstyles, and culinary trends. Ziryab never disappointed.

Up until his arrival, al-Andalus was a quite rough and tumble land. Not much emphasis was put on fashionable clothing, or other ways of looking stylish. Ziryab changed all that. He dictated that certain colors of clothing should be reserved for certain times of the year. Winter clothes should be of darker color and heavier material, with furs being an important part of outfits. Fall and Spring clothing was supposed to reflect the dominant colors of the seasons. In Fall one should wear reds, yellows, and oranges, reflecting the changing colors of the leaves. In Spring, he believed brighter colors reminiscent of the blooming flowers should be worn. In the Summer, whites and other light colors should be worn. This was the origin of the modern rule of “no white clothes after Labor Day (early September)”.

He also changed the way food was eaten in al-Andalus. Before him, no one in al-Andalus (or elsewhere in the Muslim world) cared much for food being served in courses. Different flavors and types of food from sweets to meats to salads were all served together. Ziryab dictated that there should be an order to how food is eaten. Soup was served first as an appetizer. This was then followed by the main course, which would include meats, fish, and other heavier plates. Finally, the meal was finished off by fruits and other sweets, with nuts being served afterwards as a snack. This revolutionized how chefs prepared food and how people ate. Modern multi-course meals also follow this same process today, over 1000 years after Ziryab initiated it.

Ziryab also innovated in many other aspects of dining. He was the first to recognize asparagus as an edible and tasty vegetable. He got rid of the clunky old metal goblets people had been using since before Islamic times and replaced them with lighter, more attractive crystal and glass cups, another innovation that still exists today.

He also revolutionized in terms of hygiene: Not being a man of only a few tricks, Ziryab changed the way Andalusians looked at hygiene. He was the first to introduce toothpaste to the peninsula (no doubt to the pleasure of everyone that had to talk to anyone else from close range). He was the first to suggest deodorant as a way of smelling nice, even in the hot Andalusian summers. He brought new hairstyles as well. Before his time, the people of al-Andalus (both men and women) generally had long and disheveled hair. Ziryab made popular hairstyles that kept men’s hair a little shorter and cleaner, and suggested bangs for women. These new hairstyles were managed with a new form of shampoo that Ziryab initiated that was made with rosewater and salt, leaving hair healthier than before.

As a cultural icon, his self-imposed rules about fashion, hygiene, and food quickly spread throughout the Iberian Peninsula and beyond. Throughout Medieval Europe and the Muslim world, his styles were imitated and added to existing cultures. His innovations remain today in the way we eat, dress, and take care of ourselves. He was truly a cultural icon whose styles lasted well beyond his lifetime.

Sources: https://muslimheritage.com/al-jazari-the-mechanical-genius/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zx9xsbk/revision/1

https://www.theperfumist.com/blogs/news/al-kindi-the-father-of-modern-perfumery

https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/medicine/early-islamic-medicine

Lost Islamic History