This Is Why Muslim Travelers of the 10th Century Went Back and Forth Between Spain and India

By Hassam Munir

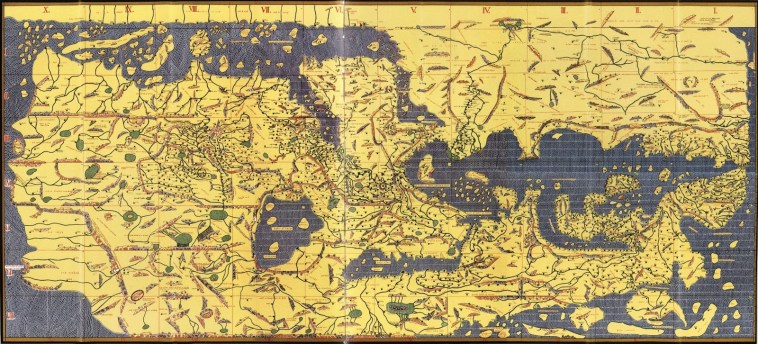

Nowadays, most of the free flow of trade, ideas, and people that once criss-crossed the Muslim world are gone, impeded by the emergence of nation-states in the past century. Though travel and communication are easier than ever thanks to modern technology, the spirit of a civilization based on a shared Islamic identity is gone. To illustrate, in this article let’s take a quick look at the flow of Spanish Muslims and products to India, and of Indian Muslims and products to Spain, in the 10th century.

From Al-Andalus to Hind

One of the travelers who just rode the waves across the Muslim world was Muhammad ibn Mu‘āwiyah, who lived in Cordoba, Spain in the early 900s. In 907, he left Cordoba, traveling exchange of knowledge and ideas. But there was once a time when this flow was flourishing all the way from al-Andalus (Spain) to Hind (India) and back, uninterrupted by politics first to Egypt and then to Makkah, Baghdād, Kūfa, and Basrah, always taking the opportunity to learn from the eminent scholars of these cities. He then moved on toward his final destination: India. He most likely came to India as a merchant. However, some sources suggest that he came seeking the cure for a qarhah (ulcer) he had developed; the doctors in Spain had been unable to treat it, and they had advised him to seek help in faraway India.

Once he was in India, Muhammad sought out a doctor who promised to cure him in exchange for all the wealth that he had brought with him (as a merchant). It probably wasn’t an easy decision to make, but Muhammad had already suffered a lot of because of his ulcer and by then he was willing to pay any price to have it removed. The doctor cured him, but then returned most of the riches that Muhammad brought to him, keeping only a fair share and saying that he had only wanted to test his patient’s love for wealth.

His trials still weren’t up. At one point, he was trying to cross a river, most likely the Indus or one of its offshoots, and almost drowned; he saved himself but most of his wealth was lost. But he was a successful merchant, and when he finally returned to Cordoba in 937, about 30 years after he had left, he had 30,000 dinars left in his purse, even after paying for the expenses of his journey home and not accounting for the value of his merchandise. He is said to have written a brief history of al-Andalus, and he passed away in June 969.

But the flow went the other way, too. Abu ‘Umar Ahmad ibn Sa‘īd (d. 1009) was known as Ibn al-Hindī because his recent ancestors had emigrated from India to Spain. He lived in Cordoba and served as the imām of the mosque of Nakhīlah. He was an expert in fiqh (jurisprudence) and Spanish history, as well as in drafting paperwork for contracts (for marriage, business, etc.). His book on this last subject is considered the most authoritative in Andalusian history. He was also an accomplished poet whom also recited poetry for the royal court.

Figs and linen

Trade flowed just as easily between the two endpoints of the Muslim world. Fruits like figs, and products like wool, linen, and glass utensils were all imported to India from Spain. Watermelons, sugarcanes, oranges, ivory, musk, aloe, and wooden armor went the other way, from India to Spain. In fact, many of the English names for these items originated in Indian languages, and followed these items into al-Andalus and, from there, into the rest of Europe. The Sanskrit word sakkar, for example, became sukkar in Arabic, then azucar in Spanish, then sucre in French and finally sugar in English. Similarly, the Sanskrit word naranj became naranja in Spanish and orange in French and English.

The revival of this kind of a flow in the Muslim world today would go a long way toward cultivating a sense of shared faith and culture. The doctors in al-Andalus knew that the doctors in Hind could treat their patient, and Ibn al-Hindī did not face much difficulty in becoming an Islamic scholar in al-Andalus. Muslims today need to actively take on cross-cultural activities, from learning new languages that are widely used among Muslims to vacationing in different parts of Muslim world. This is the key to reunite our diverse ummah.

Source: Imamuddin, S. M. (1981). Commercial and Cultural Relations Between Spain and Pak-Indo Subcontinent in the 10th Century. Islamic Studies, 20(3), 275-282.

About Hasssam Munir

Hassam Munir is a student and independent researcher of Islamic history based in Toronto, Canada. He enjoys looking into the past from fresh and diverse perspectives. He is the founder of the iHistory project, where he blogs regularly. To read more of Hassam’s work on Islamic history, visit www.ihistory.co.