Bimaristan: Islamic roots of modern hospitals

While in Europe in the Middle Ages, patients were expelled to special institutions outside the city gates, in which they were isolated from society and, mainly, depended on the mercy of wealthy benefactors, a different approach to patients was cultivated in the Islamic world, writes Dunya Ramadan.

If you read the descriptions of Arab and Persian travelers , doctors and scientists, you get the impression that hospitals in the Islamic world sometimes resembled more luxurious rehabilitation centers or spiritual oases of well-being.

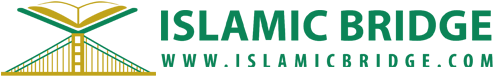

Bimaristan Nur ad-Din in Damascus, founded in the 12th century. / Source: TARKER / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

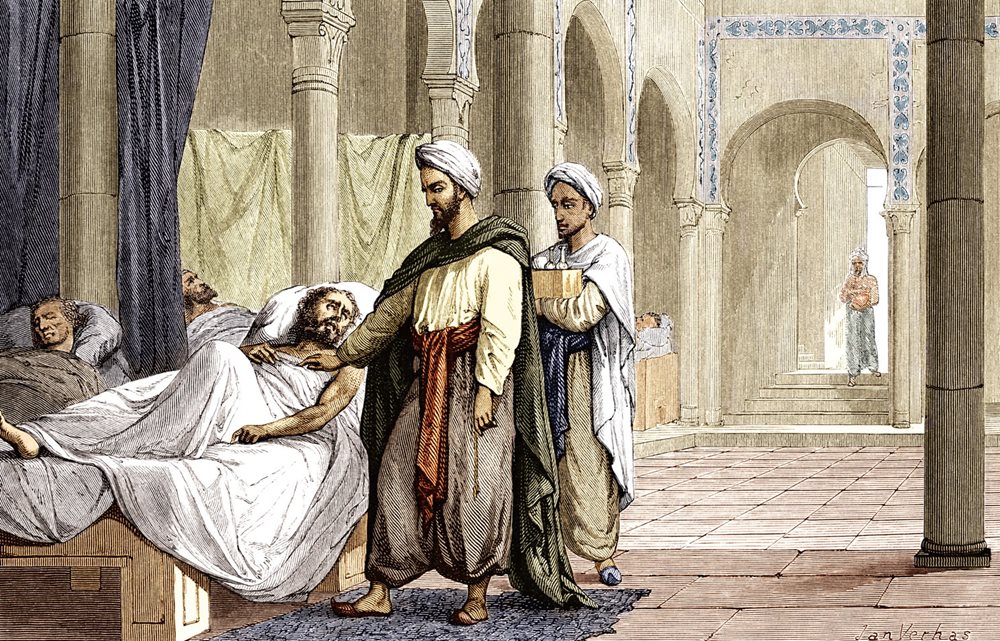

Arab poet and traveler Ibn Jubair(1145-1217) compared al-Muqtadiri hospital on the banks of the Tigris River to “a royal palace where all the amenities are offered.” During this period, hospitals or bimaristans in large Muslim metropolises such as Damascus, Cairo, Cordoba, Baghdad, experienced their heyday. The name “bimaristan” comes from Persian and can be translated as “home of the sick.” Under the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (763-809), Baghdad is said to have had several hundred hospitals. The high ethical standards applied in them make them the forerunners of modern treatment centers. It offered not only free treatment and medicine, but also food and accommodation in clean rooms. Hospitals were secularly run, with doctors treating all people regardless of ethnicity or religion. By law, they were forbidden to refuse the disadvantaged or travelers. In addition to Muslims, Jewish and Christian doctors also worked in hospitals.

Source: SHEILA TERRY / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

The charter of the bimaristan Kalown, built in the 13th century. by the Mamluk Sultan Kalown in Cairo, states: “The hospital should hold all patients, men and women, until they are fully recovered. All costs are borne by the hospital, whether people come from far away or not, whether they are locals or foreigners, strong or weak, low or high, rich or poor, employed or unemployed, blind or sick, physically or mentally ill, educated or illiterate. “

The Kalown complex in Cairo included a hospital, school and mausoleum. It was founded in 1284-1285. / Source: BERNARD DEGEORGE / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Spanish professor Victor Palleha de Bustinza writes in National Geographic History magazine that both the rich and the poor in Baghdad could be operated on by great physicians such as the Persian physician Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi .

Illustration from the European translation (13th century) of the work of ar-Razi “Comprehensive book on medicine”, depicting ar-Razi treating a patient / Source: HISTORY / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Bimaristans were divided into separate wards and departments, for example, infectious, eye diseases, for surgical and non-surgical cases. Al-Razi established the first psychiatric ward in a hospital in Baghdad, although Christendom at the time believed that mentally ill people were possessed by the devil. Men and women were housed separately and looked after by male and female staff, respectively. Most hospitals were located in close proximity to universities, so medical students accompanied doctors on rounds and took medical records.

A memorial plaque on the wall of the Argun bimaristan in Aleppo (Syria), informing about its foundation by the Emir Argun al-Kamili in mid. 14th century Mental illnesses were treated here with abundant light, fresh air and music / Source: BERNARD GAGNON

Physicians at that time attached great importance to the mental health of patients. This was also reflected in the design and atmosphere of the bimaristans, which can be found in descriptions of contemporaries or seen in surviving hospitals in Damascus or Cairo. The fountain in the green courtyard, the splash of water and the warm rays of the sun were supposed to have a calming effect on the patients. In hospitals, treatment was carried out with the help of music, for which they had their own regular musicians. Some descriptions of bimaristans also mention the scent of jasmine flowers.

The rooms in bimaristan Argun had high ceilings and contained a lot of air. Bimaristan functioned until the beginning of the 20th century. / Source: BERNARD GAGNON

Muslim doctors knew about hygiene. Before the construction of a new hospital in Baghdad, the Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtafi (875-908) asked al-Razi to find the best place for it. He hung out pieces of fresh meat in various parts of the city, and a few days later checked the degree of spoilage. The place where the meat was least rotted was named by ar-Razi the most suitable for the new bimaristan.

The fountains were central to the architecture of Argun’s bimaristan: each of the three courtyards contained a fountain around which the patient rooms were located, while the central courtyard had a large rectangular pool and well / Source: GERARD DEGEORGE / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES; NASSER RABAT / AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE / MIT

This almost utopian system functioned thanks to waqfs – charitable foundations. Paying zakat or compulsory charity is a religious duty of Muslims and is considered one of the five pillars of Islam. Thus, public hospitals were funded mainly by donations from wealthy philanthropists.

Islamosphere