As a group of leaders of the Muslim world, saved the Islamic classics from complete disappearance in the 18th-19th centuries.

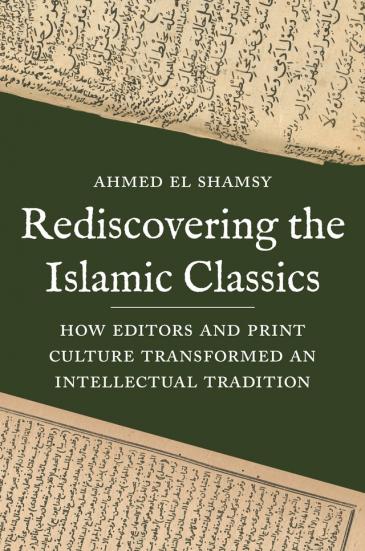

When the Mongol army under the leadership of Khan Hulagu, grandson of Genghis Khan, captured Baghdad in 1258, the Mongols plundered the precious treasures of the House of Wisdom – one of the most important academies at that time with the largest library of the Middle Ages – and threw the books into the Tigris. According to folk legends, then the river turned black from ink. The Mongol invasion marked the end of the “golden age” of Islam and the beginning of the decline of the rich Islamic intellectual tradition, writes Muhammad Nafih Wafi.

However, even during and after the Mongol invasion, some prominent figures of the Islamic world took care of the cultural heritage to the best of their ability. Although the Baghdad library was destroyed, a significant amount of Arabic manuscripts survived in other libraries of the former Abbasid empire.

But in the XIV-XIX centuries. various factors contributed to the massive loss of these books, including titles that we today regard as classics in Islamic thought.

One of the reasons was that during this period the vibrant Islamic intellectual tradition was gradually replaced by the era of textual scholasticism and epistemological esotericism. In addition, the lack of conservation methods, the delay in the introduction of printing technology , and the massive hunt for Islamic classics by Oriental scholars who sold them for huge sums to private collectors and libraries in the West hastened the disappearance of many medieval classical texts.

This is the first full-fledged publication on the impact of the print and publishing industry on Islamic scholarship, according to a statement from Princeton University Press. In it, Ahmed el-Shamsi “tells the fascinating story of how a small group of editors and intellectuals published forgotten works of Islamic literature and defined what became the classical canon of Islamic thought” / Source: en.qantara.de

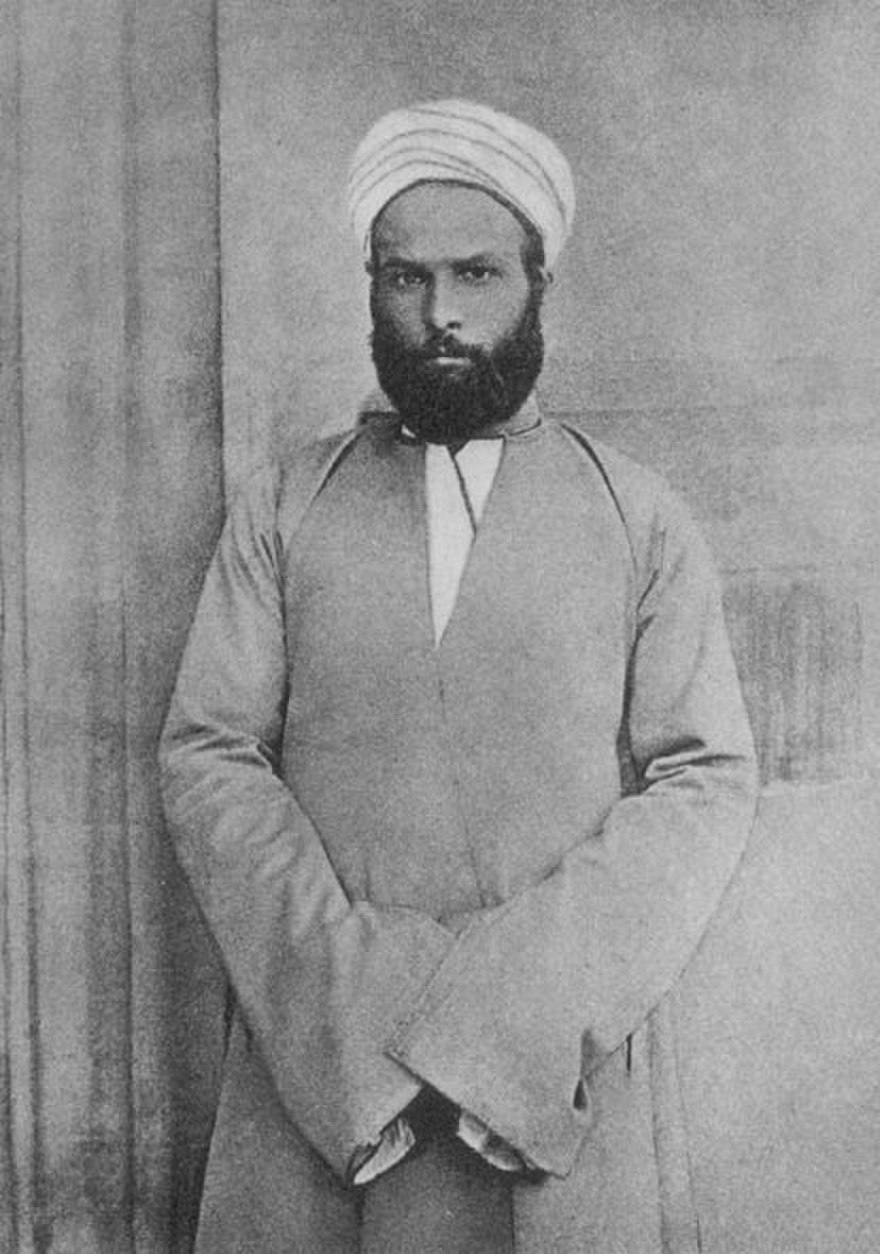

If it were not for the painstaking efforts of a small group of intellectuals in the 19th and early 20th centuries to find the remaining manuscripts and publish them, the Islamic world would have lost most of its precious classics. This initiative was accelerated by the introduction of the printing press in the Arab world, which helped the reformers in their historic enterprise. These figures, among whom were the likes of Muhammad Abdo, Tahir al-Jaziri and Muhammad al-Shawkani, did much to publish the forgotten works of Islamic literature.

For example, the Egyptian jurist Ahmed Bey al-Husseini hunted for the almost forgotten foundational writings of the Shafi’i school of law. The result was a 24-volume work titled Murshid Al-Anam li-birr Umm al-Imam, a comprehensive commentary on Imam Shafi’i’s al-Umma. Ahmed Bey also organized and financed the publication of the 17-volume al-Umm, which came out between 1903 and 1908. Two centuries before its rediscovery thanks to al-Husseini, Kitab al-Umm, like many other classics, was almost completely forgotten and ignored by readers. Even Shafi’i jurists did not consider it necessary to read the own writings of Imam Shafi’i.

Muhammad Abdo / Source: thereaderwiki.com

In addition to “al-Umm”, the manuscripts, which were given a new life, included some of the fundamental works of the Arab-Islamic world: “Grammar” al-Sibaveikhi (VIII century), interpretation of the Koran at-Tabari (XI century), theology al -Ashari (X century), the Sufi treatise of al-Makki (X century) and the sociology of history of Ibn Khaldun (XIV century).

Most of these works were rare and difficult to obtain in the 19th century, when Islamic scholarly discourse reveled in technical commentaries on earlier works, usually written centuries after the original works. This trend in textual orthodoxy, which prevailed in the Islamic world after the 16th century, limited scholarly discourse to a few popularized texts. Scholars of the time preferred to engage in textual truncations of these commentaries, as well as the compilation of marginal notes and footnotes, while the originals remained gathering dust in book depositories or were appropriated by libraries in the West.

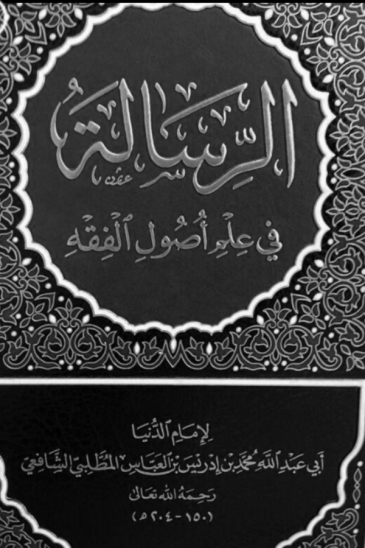

The modern edition of the legal treatise by ash-Shafi’i “Risal” (IX century), the fundamental work on the principles of Islamic jurisprudence. According to Ahmed el-Shamsi, the works of al-Shafi’i, a Muslim scholar and theologian, were among those manuscripts that the reformers gave new life / Source: en.qantara.de

Therefore, the fundamental works written by the founders of various schools of Islamic law, theology, philosophy, linguistics, Sufism and historiography were consigned to oblivion. And this was compounded by a growing esoteric trend that promoted spiritual illumination as the highest form of knowledge acquisition. The Islamic world’s ignorance of its own classical heritage was combined with inadequate funding and an inadequate system for the storage and protection of manuscripts.

Therefore, the reformers had to overcome enormous obstacles, they required enormous philological, organizational and financial resources, as well as considerable time and effort. They had to find and acquire manuscripts, put together complete works from disparate fragments, decipher the texts, despite errors and damage, and understand their meaning without being able to resort to adequate reference material, etc. As a result of this activity, classical works that had been relegated to the background throughout the “post-classical” period began to appear in large numbers in academic and scientific discourses, leading Islamic scholarship throughout the region to revival and reform.

The fascinating history of these reformers and their contribution to the revival of classical Arab-Islamic scholarship is the focus of Ahmed al-Shamsi’s recent English-language book Re-discovering Islamic Classics: How Editors and Print Culture Transformed Intellectual Tradition.

Al-Shamsi writes that the revival of classical literature was part of a broader set of sociocultural changes in the Muslim world, often referred to as nahda (lit .: revival). He argues that the renaissance in the Islamic world was not about the abandonment of the Arab-Islamic intellectual tradition in favor of imported modernity, but the reformers turned to the classical tradition to question the post-classical tradition, which they declared limited and ossified.

Islamosphere