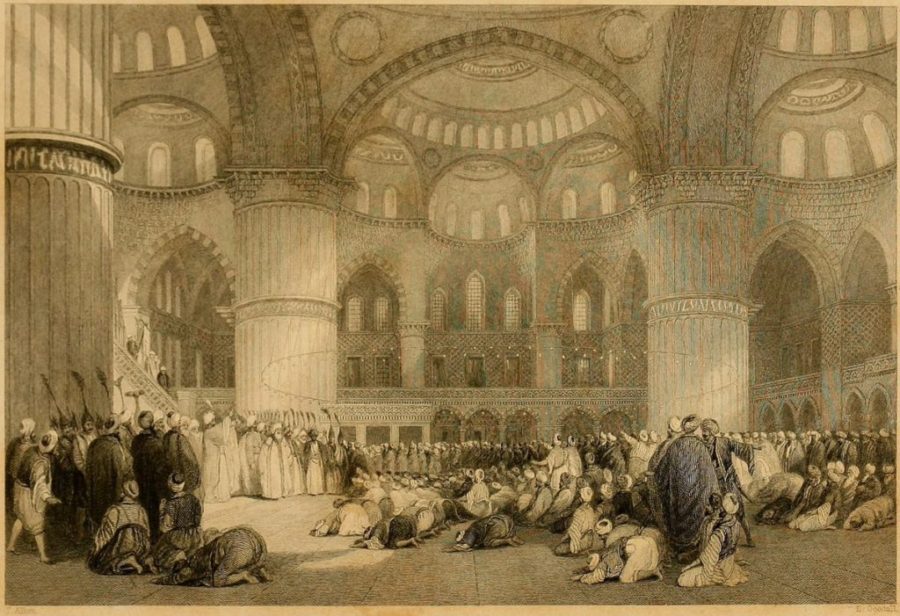

Khutbah as a political instrument

In the Middle Ages, the Friday sermon or khutbah carried not only religious but also political significance, writes Mustafa Baktyr for İslam Ansiklopedisi.

Khutbah is a speech or sermon that is addressed to the community during certain services, in particular, before Friday and holiday prayers.

After the death of the Messenger of Allah (peace be upon him), the khutba, along with religious significance, acquired political significance. When Abu Bakr (may Allah be pleased with him) was elected caliph, then, ascending to the minbar , he addressed the audience with a sermon, in which he explained the basic principles of the policy that he was going to follow. The next three caliphs did the same. Similar speeches were made by the governors (wali) when they took office. On the other hand, at first the caliph not only pronounced the Friday khutba, but also led the prayer.

In the subsequent period, the expansion of territories, the influence of the Sassanian traditions on the state organization and the growth of official duties led to the fact that the caliphs began to keep away from the people. Therefore, officials began to be appointed to pronounce the Friday khutbah and conduct namaz, and the names of the caliph and sultan were mentioned in the khutbahs as symbols of sovereignty and independence.

Source: islamansiklopedisi.org.tr

For the legitimacy of the power of any ruler, it was necessary that it be confirmed by the caliph. And the first condition for this was that this ruler ordered in mosques to pronounce khutba in honor of the caliph. In the east of the Islamic world, this was done in honor of the Abbasids, sometimes in honor of the Fatimids. In the states of the Karakhanids, Ghaznavids and Seljuks, the khutba was pronounced in honor of the Abbasid caliphs.

The significance of the khutbah in terms of politics was that it indicated the balance of power between the caliph on the one hand and the sultans, governors, and local dynasties on the other. The ruler of Khorasan and the founder of the Takhirid dynasty, Tahir ibn Hussein, became the first governor (wali), who in 822 ordered the khutba to be recited in his honor, and not the caliph al-Mamun as a sign of independence. Since the recognition of the caliph meant the recognition of the supremacy of the governor of the province, whose name was mentioned in the khutba along with his name, some dynasties preferred not to recognize the caliph. For example, the Samanidsdid not recognize the caliphate of al-Muti Lillah (946-974), so as not to recognize the superiority of their regents from the Buyid dynasty. However, to legitimize their power, they recognized the Caliph al-Mustakfi Billah and even after his death continued to mention his name in the khutbahs.

The name of the ruler of a provincial dynasty was sometimes mentioned in the khutba along with the name of the caliph. This gradually resulted in a tendency to recognize the caliph as a spiritual leader and the ruler as a political one.

Source: islamansiklopedisi.org.tr

The khutbahs from time to time reflected the balance of power between states. The Abbasid caliphs, especially during the struggle for the throne, pronounced khutbahs on behalf of the party that dominated Baghdad. For example, Caliph al-Mustazhir Billah in 1099 ordered to pronounce khutbas on behalf of the Seljuk sultan Muhammad Tapar, declaring him the rightful ruler. When the army of Barkiyaruk approached Baghdad the following year , they began to pronounce khutbahs in his honor.

The adoption of Islam by the Mongols, who put an end to the Abbasid caliphate, brought about a change in the khutbas. The rulers from the Mongol dynasties, who did not recognize the Abbasid caliphate in Egypt, pronounced khutbs in honor of the four righteous caliphs, if they were Sunnis, and in honor of 12 imams, if they were Shiites. The same practice took root under the Great Mughals in India. In Mamluk Egypt, khutbs were pronounced in honor of the Abbasid caliphs of Egypt, who had no political power, and the Mamluk rulers.

Sometimes weaker states pronounced khutba in honor of the ruler of a stronger state in order to enlist his patronage. For example, during the heyday of the Ottoman Empire in the small Muslim states of Aceh, Java, Sri Lanka, Sumatra, the khutba was pronounced in honor of the Turkish sultan… Sometimes this was done even in those territories that left the Ottoman Empire. For example, when the Crimean Khanate was proclaimed independent according to the Kyuchuk-Kaynardzhi peace treaty, it still remained religiously and spiritually attached to the Ottoman Empire, so Friday and holiday khutbs were pronounced in honor of the Turkish sultan. Since later the power of other Muslim rulers weakened, the latter began to be recognized as the caliph of all Muslims, and a similar practice in the second half of the 19th century. entrenched in a vast territory from India to the Far East and Africa.

Source: islamansiklopedisi.org.tr

Islamosphere